| David Drake's Life

David Drake was born into slavery in about 1801. Records show that he was "country born," which means that he began life not in Africa but in this country. His first known owner was Harvey Drake, a young man of Edgefield District, South Carolina. Harvey was in business with his uncle, Dr. Abner Landrum, who had opened a pottery factory just a mile outside the town of Edgefield. Dr. Landrum created a village, which he called Pottersville, around the enterprise.

Young Dave was put to work in the factory while he was still in his teens and taught how to turn stoneware vessels —jugs, pitchers, churns, storage jars—all in great demand on plantations across South Carolina. Though Pottersville has since disappeared, the spot where he fired his pots is still visible at the site. The trees in the photograph above mark the kiln's location.

At the same time that Dave Drake was learning how to turn and burn stoneware, he was acquiring another, very different skill. He was learning how to read. The sharing of such knowledge with the enslaved population had long been frowned upon by the slaveholders of South Carolina, who believed that even the slightest education would cause a slave to think and act on his own, thereby becoming more likely to rebel. Some in the state nevertheless chose to teach their slaves to read so that they could have direct access to the Bible. Because Harvey Drake was a profoundly religious man, it seems likely that it was he who started young Dave on the road to literacy, perhaps using Noah Webster's "blue-back speller," a page of which is shown at left. At the same time that Dave Drake was learning how to turn and burn stoneware, he was acquiring another, very different skill. He was learning how to read. The sharing of such knowledge with the enslaved population had long been frowned upon by the slaveholders of South Carolina, who believed that even the slightest education would cause a slave to think and act on his own, thereby becoming more likely to rebel. Some in the state nevertheless chose to teach their slaves to read so that they could have direct access to the Bible. Because Harvey Drake was a profoundly religious man, it seems likely that it was he who started young Dave on the road to literacy, perhaps using Noah Webster's "blue-back speller," a page of which is shown at left.

We know that Dave Drake knew how to read and write because he wrote inscriptions on many of his pots. Often he made them rhyme. This is his first known poem, written on a Pottersville jar dated July 12, 1834:

put every bit all between

surely this Jar will hold 14

Writing this short set of instructions in how to pack a fourteen-gallon jar with meat may seem a simple thing, but it was in fact an extraordinary act of courage for a slave at that time. Dave was telling the world of Edgefield that he could read words, he could write words, and he could even make words rhyme. Only a few months after he composed this poem, the South Carolina General Assembly—as if outraged by what he had done—passed the harshest anti-literacy law in the state's history. As former South Carolina slave Elijah Green remembered, "An' no for God's sake, don' let a slave be catch with pencil an' paper." It was, he said, "a major crime."

When Harvey Drake died, Dave was purchased by Harvey's brother, Reuben, who decided to take his family west to newly opened land in northern Louisiana. He might have taken his excellent potter with him if a terrible accident had not occurred. We know about the event from notes made by Laura Bragg, Director of the Charleston Museum, during a research trip to Edgefield in 1930. Carey Dickson, a retired Black pottery worker, told her, "Of course I knew Dave. I know all about him. He used to belong to old man Drake and it was at that time that he had his leg cut off. They say he got drunk and layed on the railroad track."

Dave survived, but he had to stay behind as the other Drake slaves, probably including loved ones, set off for Louisiana. He was purchased by Rev. John Landrum, who was another uncle of Harvey and Reuben Drake, and taken twelve miles across the district to the headwaters of Horse Creek, a tributary of the Savannah River. There, he was put to work in a pottery owned by Reverend John. Because Dave was no longer able to operate the foot treadle that moved the potter's wheel, he teamed with another slave, Henry, whose arms were crippled but whose legs were strong enough to drive the wheel. What an image: two men, both damaged, helping each another remain productive, the only real measure of worth under the slavery system. It must have worked, for Louise Landrum Murphey, the great-great- granddaughter of Reverend John, remembers her father saying, "Dave was the best potter they had in there."

It appears that Reverend John lent the potter at this time to his new son-in-law, Lewis Miles. Lewis, who lived near his in-laws at Horse Creek, was learning the pottery business, and Dave Drake surely had much to teach him. His inscriptions are a record of their collaboration. Beginning in January of 1840, he wrote Lewis Miles's name on his pots. Astonishingly, he also wrote his own name. No slave potter in all the years of pottery making in Edgefield had ever done such a thing. After that first time, he often signed his work, though by no means always. Many perfectly good vessels bear only a date and "Lm," for Lewis Miles. Some pots that have been attributed to him carry no marks at all. But on those occasions when he chose to write "Dave" in the damp clay, it was almost as though he were imprinting the jar with his soul.

The potter appears to have fallen in love when he came to Horse Creek. This is suggested by two poems that he wrote in 1840. The first, dated February 10, reads,

whats better than Kissing —

while we both are at fishing

The second, written on August 26, reads,

another trick is worst than this +

Dearest miss: spare me a Kiss +

It may be that Dave Drake and the woman he was attracted to were allowed to marry. Though not a legal marriage, it would have been marked by a ceremony in which the participants jumped together over a broomstick, a custom that was common in Southern slavery at the time. It may be that Dave Drake and the woman he was attracted to were allowed to marry. Though not a legal marriage, it would have been marked by a ceremony in which the participants jumped together over a broomstick, a custom that was common in Southern slavery at the time.

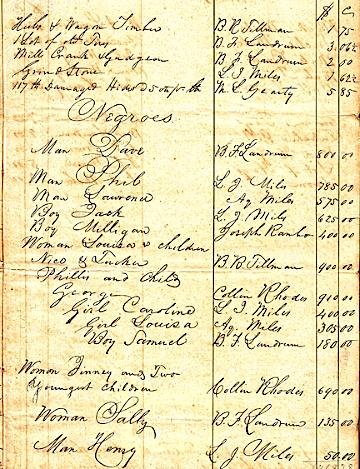

When Reverend John died in December of 1846, all eighteen of his slaves were put up for sale, including Dave and possibly his "Dearest miss." The record of the sale is shown at left. Whatever links of love and kinship existed among Reverend John's slaves were severed by the sale, for his slaves were divided among six different buyers. Years later, in 1857, Dave Drake composed a poem that suggested he was still thinking of what happened on that dreadful day:

I wonder where is all my relation

friendship to all — and, every nation

The potter was purchased at the sale by Reverend John's son, Franklin Landrum. This was the beginning of one of the most difficult periods in Dave Drake's life. He was faced with a series of events, including three murders, that strained relations between the slaves and slave owners of the area. Perhaps most difficult for Dave was the suicide of one of the women who worked in the pottery with him, following her whipping by Franklin Landrum. What a disturbing, complicated time this whole period of anger and punishment and treachery must have been for the families, slave and free, at Horse Creek. No poems by Dave Drake have been found from this period, which has led many to suspect that he was forbidden to write. If he had been able to write freely on his jars at this time, what terrible images he would have had to draw on.

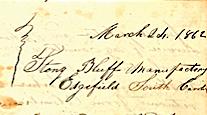

Lewis Miles acquired ownership of the potter in 1849. He brought him to a fine new pottery, which he had built on his land and named Stony Bluff. The full name of the factory is shown in the letter heading at right. With Henry, the worker with crippled arms, probably again turning the foot treadle for him, Dave produced work that gained a reputation for being the "best ware in [the] country." It was loaded in wagons and peddled all over Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina. Lewis Miles acquired ownership of the potter in 1849. He brought him to a fine new pottery, which he had built on his land and named Stony Bluff. The full name of the factory is shown in the letter heading at right. With Henry, the worker with crippled arms, probably again turning the foot treadle for him, Dave produced work that gained a reputation for being the "best ware in [the] country." It was loaded in wagons and peddled all over Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina.

At Stony Bluff, Dave Drake began to write poems again. His surviving poems increased from one every few years to three in 1857, eight in 1858, and seven in 1859. He sent his verses into the world one after the other, in one case writing two in the same day.

About 1856, Lewis Miles began to worry as issue after issue arose to divide the country. Knowing that paper money could become worthless if war broke out between North and South, Lewis turned to pottery to protect his family. He instructed Dave to make a little stoneware container for him each month, a miniature version of the great jars the potter was known for. Lewis filled each one with gold and buried it.

When war came in 1861, every eligible male in the Miles and Landrum families volunteered for military duty. Though many slaves from the area accompanied the sons of their owners to war or were conscripted to build fortifications around endangered cities, Dave Drake, sixty years old and missing a leg, was kept at Stony Bluff to work in the factory. Jars that he made for Lewis Miles survive from every year of the war except the final one. He wrote his last known poem on May 3, 1862, on a twenty-inch-high storage jar that, in spite of the emotional and physical disruptions of wartime, is almost perfectly formed:

I, made this Jar, all of cross

If, you dont repent, you will be, lost =

Reading this couplet in the context of the war, it is hard not to hear it as a Cassandra-like warning. Accounts of death and disaster were everywhere at the time that he wrote it. In the single battle of Shiloh, fought a month earlier, more men died than all the Americans who died in the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, and the Mexican War combined. This gives terrible weight to the words "you will be, lost."

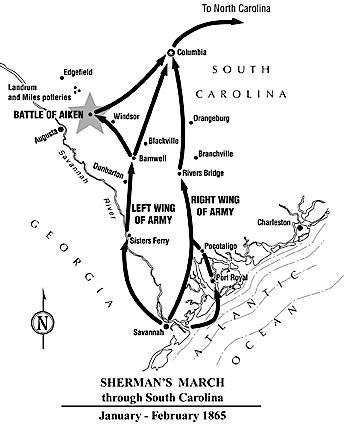

When Sherman led his men from Savannah through South Carolina, one branch of his army seemed headed directly for Edgefield and for the potteries at Stony Bluff and Horse Creek.The path of the army is shown in the map below. The Yankees were stopped only  when the forces of Gen. Joseph Wheeler hid themselves behind the shops and houses of nearby Aiken, surprised the invaders, and drove them from the area. Though a small incident in the great panorama of the war, the Battle of Aiken, as it came to be called, had real importance in Dave's story: it spared the pottery factories where he had long worked and saved many of the documents that have shed light on his life. when the forces of Gen. Joseph Wheeler hid themselves behind the shops and houses of nearby Aiken, surprised the invaders, and drove them from the area. Though a small incident in the great panorama of the war, the Battle of Aiken, as it came to be called, had real importance in Dave's story: it spared the pottery factories where he had long worked and saved many of the documents that have shed light on his life.

After the war, the potter was a free man. He took the name David Drake, which was a reference to his early life at Pottersville. With legal surnames now to unite them, many former slaves sought to locate relatives from whom they had been separated. Often, members of extended families chose to live close to one another in kinship colonies. Records from the 1870 U. S. Census suggest that such a colony grew up around David Drake, perhaps uniting him with children and grandchildren.

He would need this support, for the last few years of his life were fraught with danger as members of the Ku Klux Klan rode the district. On one night they raided his neighborhood and severely beat a black woman who lived there.

David Drake died at some point in the mid-1870s, for his name does not appear on the 1880 Census. Because this was not a prosperous time for Blacks in Edgefield, his family members probably could not afford to purchase a marker for him. It's likely that they marked his grave instead with pieces of broken crockery, which was then a practice in much of the Black South. Drake's grave might, in fact, have been covered with sherds of a jar that he himself had made. Perhaps his final marker was a fragment of stoneware with "Dave" written on it in his own hand.

Information on this page is condensed from Carolina Clay: The Life and Legend of the Slave Potter, Dave by Leonard Todd (W.W. Norton). The photograph of the Pottersville site is by the author. The woodcut and alphabets are from Noah Webster's The American Spelling Book, 1824 edition, courtesy of Applewood Books, Carlisle, Mass. The L. Miles inscription is on an 1841 jug in a private collection; the inscription photo by Gavin Ashworth is courtesy of Ceramics in America. The 1847 slave sale record is in the estate papers of Rev. John Landrum at the Edgefield County Archives. The 1862 Stony Bluff letter is in the Sylvester Bleckley Papers at the South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina. The map of Sherman's March is by Jo Ann Amos.

|